By Rachel DaDamio

December 2, 2024

I love the team aspect of NCAA cross country. In their pre-race huddle at the championship meet, most coaches probably share some variation of “every point counts” with their team. Every runner, whether they finish in the top 10 or farther back in the pack, sprints up the hill to the finish of the Thomas Zimmer cross country course to secure precious points for their team.

A team’s score in a cross country meet is the sum of the places of its top 5 runners, and teams are ranked by the order of their scores from smallest to largest. At the NCAA championship meet, there are 40 individual competitors in the race, and these athletes are excluded from the team scoring. For example, if an individual competitor were to win the race and the runner-up were part of a team, the second place athlete would score 1 point in the team scoring.

However, the method of scoring in cross country can feel arbitrary - why do we use place instead of time? Why do we include 5 runners instead of 4, 6, or 7 runners? I wanted to see who would win cross country nationals using alternative methods of scoring.

Including 6th and 7th runners in the score:

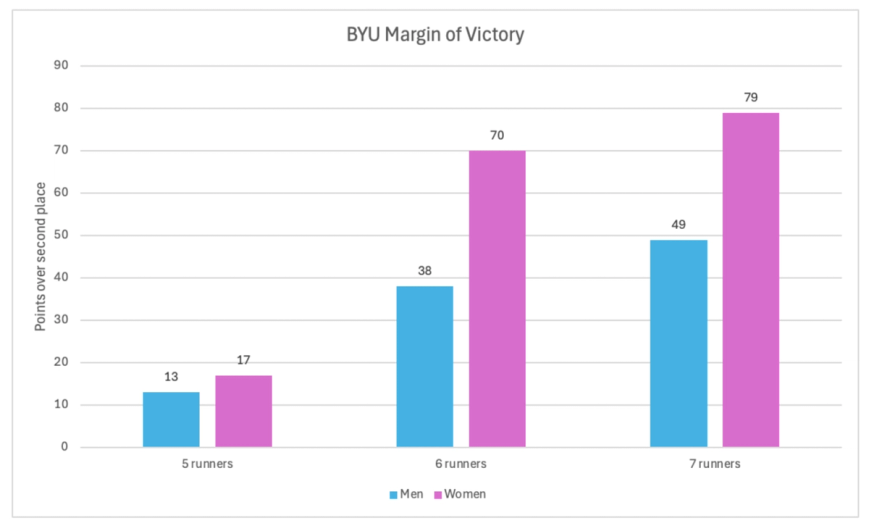

BYU’s strength is in their depth on both the men’s and women’s side, and the Cougars get more dominant when we include 6th and 7th runners in the score. Using traditional scoring, the BYU women beat runner-up West Virginia by 17 points, and the men won by 13 points over Iowa State.

However, when we include 6 runners in the score, the BYU women’s margin of victory jumps to 70 points over would-be runner up Northern Arizona. When including all 7 runners in the score, BYU wins by 79 points over NAU.

The BYU and Iowa State men hold the top two positions when we include the 6th and 7th runners, but BYU wins by a larger margin as we include more runners. When including 6 runners, BYU wins by 38 points, and when including all 7 runners, their margin of victory becomes 49 points.

Flight scoring:

Traditionally, all runners compete head-to-head in a cross country race and have a score equal to their overall place (excluding the individual competitors). As another alternative method of scoring, we implemented “flight scoring” for the NCAA championships. We scored the first runners of every team against each other, then the second runners, then the third runners, and so on. This method of scoring measures how well a team’s runners stack up against their peer group.

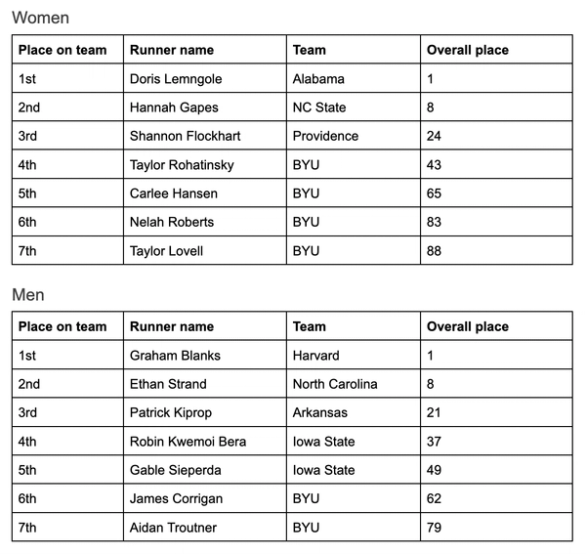

In this alternate universe, BYU, Iowa State, and Arkansas still finish top 3 in the men’s team results. However, North Carolina sneaks on the podium (originally finishing 6th) thanks to their second runner Ethan Strand finishing 8th overall – first among all second runners.

Flight scoring shakes up the results a little more on the women’s side, with BYU and West Virginia swapping first and second place. Providence would still finish in third, but Stanford, like North Carolina on the men’s side, would move from 6th to 4th place. Notably for the Cardinal women, Zofia Dudek finished 3rd among all fourth runners.

Even though the BYU women did not win with flight scoring, they had the best fourth (Taylor Rohatinsky), fifth (Carlee Hansen), sixth (Nelah Roberts), and seventh (Taylor Lovell) runners in the field. The BYU men had the best sixth (James Corrigan) and seventh (Aidan Troutner) runners in the field. These impressive finishes help explain how BYU became more dominant as we included more runners in team scoring.

Top runners by place on team:

Time-based scoring:

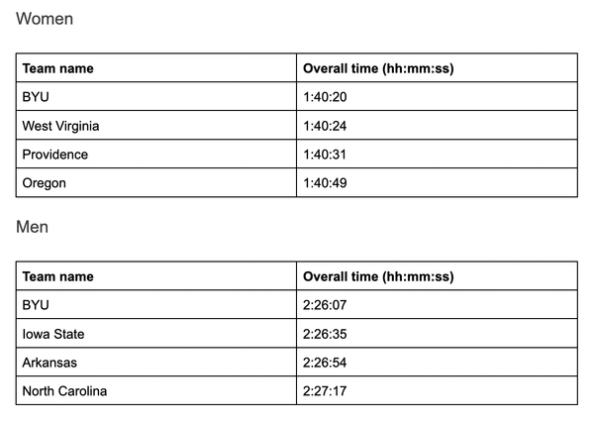

Instead of taking the sum of the top five runners’ places, we could alternatively take the sum of their times. When implementing time-based scoring, we see the same first through third place finishes on both the men’s and women’s side. However, like in flight scoring, North Carolina would move from fourth to sixth place. For the women, Oregon would have moved from fifth to fourth place to make the podium.

Smallest spread:

In cross country, a team’s “spread” is the difference in place or time between their first and fifth runner. While there is no award for having the smallest spread, it is often viewed as a positive since it means your team is running as a pack.

Time spread:

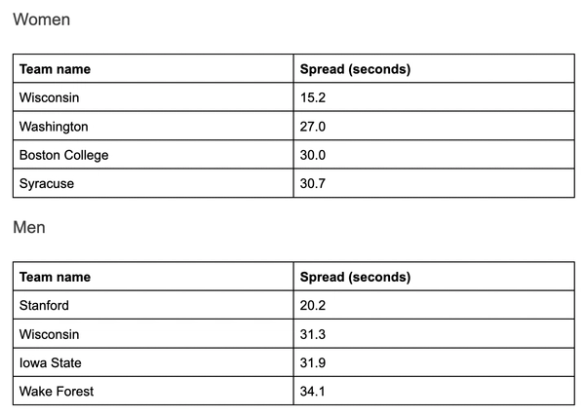

The Badgers excel at running as a pack - on the women’s side, Wisconsin had the smallest time spread between its first and fifth runners (15.2 seconds), and on the men’s side, they had the second smallest spread (31.3 seconds).

Place:

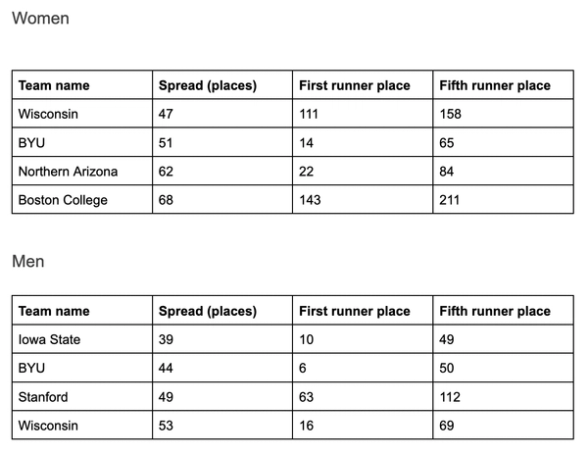

Wisconsin and BYU stand out when it comes to place spread, with both their men’s and women’s teams having a relatively small spread in place. Notably, Iowa State, who finished second overall to BYU, had the smallest place spread on the men’s side with only 39 places separating their first and fifth runners.

Conclusion:

Ultimately, BYU's excellence is evident no matter how we score the NCAA championships. When using traditional scoring, including more runners, flight scoring, or time-based methods, the Cougars proved their depth, pack strength, and consistency. Still, in a sport where every place and every second matters, these alternative scoring methods shuffle the podium a bit and add an extra layer of intrigue to the team dynamics we love about cross country.

Full results with alternative scoring.

___________________

Keep up with all things track and field by following us across Instagram, X, Bluesky, Threads, and YouTube. Catch the latest episodes of the CITIUS MAG Podcast on Spotify and Apple Podcasts. For more, subscribe to The Lap Count and CITIUS MAG Newsletter for the top running news delivered straight to your inbox.

Rachel DaDamio

Rachel DaDamio ran at the University of Notre Dame and moved to Chicago after graduating to work as a data scientist, where she’s also training for a fall marathon.