By Audrey Allen

September 11, 2024

By Audrey Allen, David Melly, and Paul Hof-Mahoney.

Any fan of collegiate cross-country is aware of the dynamics that the two-kilometer-sized gender disparity in race distances creates and perpetuates. The men race 8K and the women race 6K, then the gap widens in the postseason when the men move up to 10K for regional and national meets. Some might call this divide the result of tradition, but it’s only 20ish years old – the last increase in distance we got was tacking that last kilometer onto the women’s 5K back in 2000. So with golf courses around the country getting a mow and top-sevens dusting off their spikes to kick off the fall season, it’s worth revisiting how we got here and where we might go.

Women’s distance running looks very different now than it did in 2000. The 5000m world record was 28 seconds – almost half a lap of the track! – slower than it is today. And the seismic changes over the last decade or so were solidified in a year where the Caitlin Clark of track and field, Parker Valby, put the NCAA records in the 5000m and 10,000m under 15 and 31 minutes, respectively, for the first time in history. The greatest miler in the world, Faith Kipyegon, is also the reigning World champion and Olympic silver medalist at 5000m, and women running sub-29 minute 10Ks on the roads and the track is now a thing.

So why hasn’t NCAA cross country gotten the memo that this particular wing of the sport has leveled up?

We’ve all heard the usual arguments for equalization: women shouldn’t be held to lower standards, there’s a gendered gap that exists in the extra 10 minutes or so of screentime the men get in the spotlight at NCAAs, and it’s a pain in the ass for meet directors to map out two separate courses. The simple solution would be to standardize everything.

But where to equalize is a more interesting question. The USATF and World XC championships on the pro level contest both races over 10K. The obvious choice would be to do what NIL and pay-to-play have done in other sports – make everything on the collegiate level look as similar to the pros as possible since we’re increasingly blurring the lines between amateur and professional competition anyway.

But there’s one big flaw: a national championship to determine the best runner in the country over 10 kilometers already exists; it just happens to be contested over 25 laps during the outdoor track season. There are different skillsets and strengths for grass and hill specialists versus track runners, but doesn’t making everyone run 10K in cross-country more or less replicate the same outcomes with the same people? Whereas over 6K, strength-oriented milers and low-volume 5000m runners have a fighting shot – and in the spirit of pure racing, embracing an “off-distance” lowers the annoying emphasis on time comparisons.

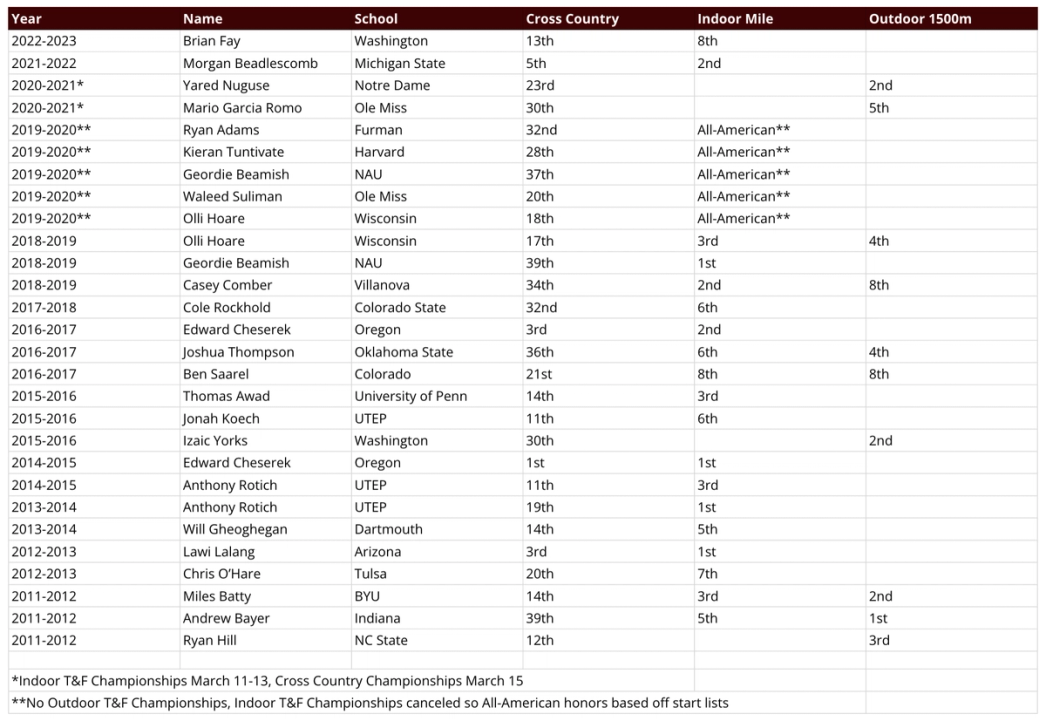

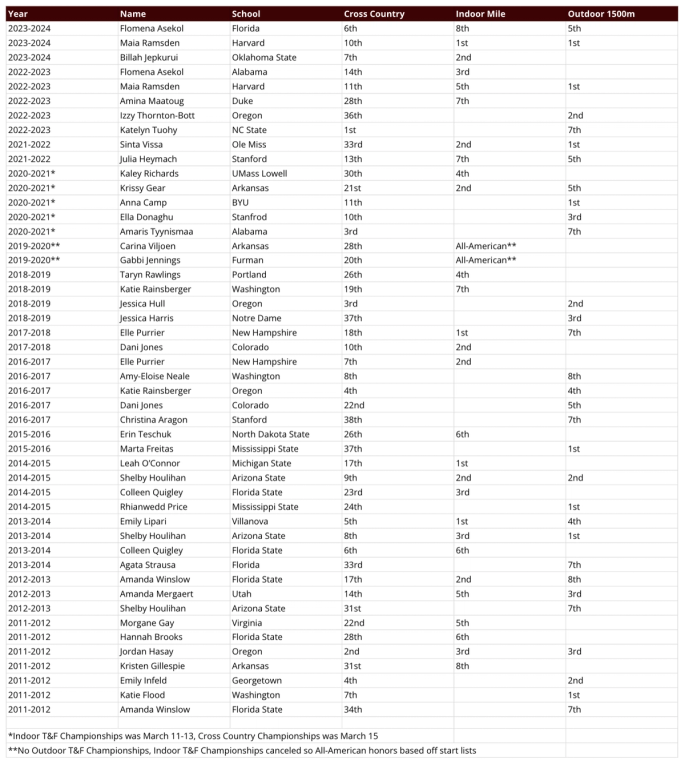

In theory, standardizing at 6K should make championships more broadly competitive. But in practice? With help from CITIUS MAG statistics junkie Paul Hof-Mahoney, we looked at all the runners over the last 14 seasons (the last time the All-American criteria was updated) who accomplished the double feat of First-Team All-American honors in either the mile indoors or 1500m outdoors AND cross country.

The numbers show that the 6K distance is far more inclusive of a broader range of running talent from mid-distance to distance relative to the 10K race. Dating back to the 2011-2012 season, 28 men accomplished this feat compared to 48 women. Nearly twice as many women finished top 40 at NCAA XC and top 8 in either the mile or 1500m in the same academic year.

13 of the last 26 women’s mile/1500m champions were also cross country All-Americans that year as opposed to only five men. In the 2023-2024 academic year, no males were added to this list (but kudos to Liam Murphy of Villanova, who was 14th at cross country nationals and earned Second-Team All-American honors in the outdoor 1500m) whereas Oklahoma State’s Billah Jepkurui, Harvard’s Maia Ramsden, and Florida’s Flomena Asekol all put their versatility to good use.

“But racing only 6K will churn out soft pro runners ill-prepared for the big dance!” In fact, the opposite is true. Many of the most accomplished pros on the scene right now, including Olympic medalists Yared Nuguse and Jessica Hull and World Indoor champions Geordie Beamish and Elle St. Pierre, are double All-Americans who’ve found success at a range of distances and surfaces. One odd Duck (pun intended) is Edward Cheserek of Oregon, the only person since 2011 to win a cross country title and either the mile/1500m in the same academic year (2014-2015). But you don’t rack up 17 NCAA titles without having more than the usual number of tools in your racing toolbox.

Over time, as the depth of women’s sports increases more broadly with increased participation rates and more international talent coming to the U.S., the trend – that women’s NCAA XC races are actually more competitive than men’s – will likely only continue absent change. In many ways, the female side of the sport is a higher-stakes race, since there’s less time for the aerobic monsters to run away from the field and more fast-twitch kickers in contention late, which consequently is… more fun, and more entertaining.

In short, the much-maligned 6K is underrated and deserves its spot at the top of women’s cross country. Take notes, boys.

Audrey Allen

Audrey is a student-athlete at UCLA (Go Bruins!) studying Communications with minors in Professional Writing and Entrepreneurship. When she’s not spiking up for cross country and track, she loves being involved with the media side of the sport. You’ll often find her taking photos from the sidelines or designing graphics on her laptop.