By Rachel DaDamio

July 5, 2024

After the women’s 800m final at the U.S. Olympic Trials this past weekend, track fans were bombarded with comments like, “our qualifying system is broken,” and “we don’t always send the best teams to the Olympics.” The Olympic Trials are undeniably ruthless — securing a spot on Team USA for Paris requires not only hitting a qualifying standard or earning a suitably high World ranking, but also finishing in the top three of your event. To even get that chance, athletes must navigate through the rounds without any mishaps. No exceptions are made, not even for a reigning Olympic champion. This high-stakes system, where anything can happen on race day, is often seen as unpredictable — but is it really?

“The rounds,” or the preliminary races before the final, are big talk at the Olympic Trials for a couple of reasons. First, the pros don’t typically run prelims at regular season meets — they are reserved for championship races. Second, having rounds introduces new tactics not present in straight-to-final competitions. It’s a delicate balance. An athlete must race well enough in the rounds to advance to the final while still conserving energy. No one wants to run their best race in a semi-final.

There are a few factors at play in approaching preliminary rounds:

- Winning a prelim = confidence boost and good momentum for future races.

- For shorter races (800m and below), winning and running fast in the prelim results in a better lane position in subsequent rounds.

- Shorter races provide less time for athletes to be tactical.

- Winning a prelim could involve unnecessary effort that might take away from an athlete’s performance in the final.

I wanted to investigate how the eventual top three athletes perform in the rounds. Do they conserve as much as possible for the final? Or do they go for the win, even if it isn’t necessary for qualification?

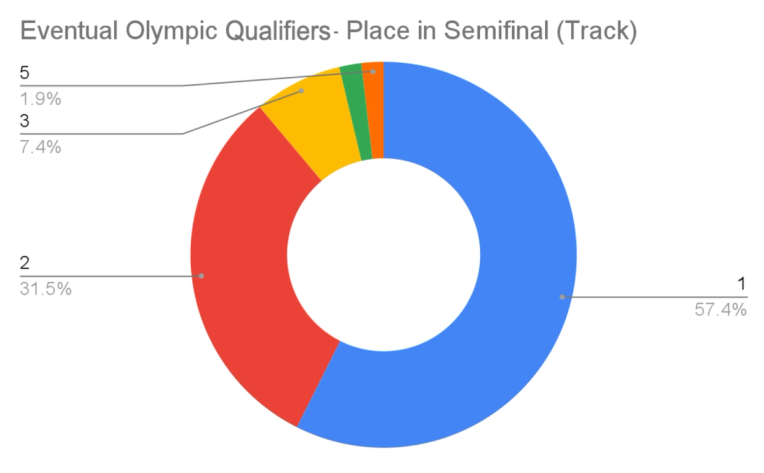

The common narrative around the Olympic Trials is that they’re thrilling and exciting because of the upsets, especially compared to other countries where there are selection committees or discretionary spots. However, the data shows that the final qualifications are largely predictable. In the 18 track events with a semifinal (all track races aside from the men’s and women’s 10,000m), the lowest place through the rounds by an eventual Olympic qualifier was fifth (Elle St. Pierre, in the women’s 1500m). In almost 90% of cases, the eventual qualifiers placed either first or second in their semifinal heat.

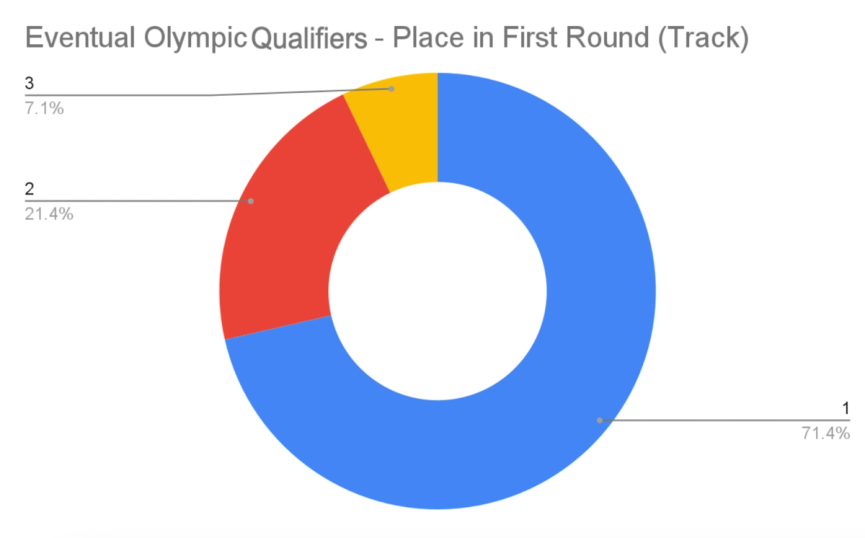

When we look at the same chart for the 14 events with more than one preliminary round (all track races aside from the men’s and women’s 10,000m, 5,000m, and 3,000mSC), the trend of prelim winning is even more prevalent. 71% of Olympic qualifiers win their first round race (compared to 57% above), and the lowest place by an eventual qualifier in the first round is third.

When we limit the above charts to only include eventual US champions, 83% take first in their semifinal and 86% take first in their first round heat. Kendall Ellis (women’s 400m), Nia Akins (women’s 800m), Nikki Hiltz (women’s 1500m), Valerie Constein (women’s 3000m steeple), and Grant Fisher (men’s 5000m) are the only US Champions that were beaten in an earlier round.

The above trends call Nia Ali’s 100mH strategy into question. The 2019 World Champion and 2016 Olympic Silver medalist jogged her first round heat to finish last by over five seconds. Ali’s approach for the first round was understandable: due to scratches all athletes, regardless of their time or place, would qualify for the semi-final. However, looking at the data, it’s clear that most Olympic qualifiers are treating the early rounds competitively. Ali missed the Olympics by one place, finishing fourth in her final.

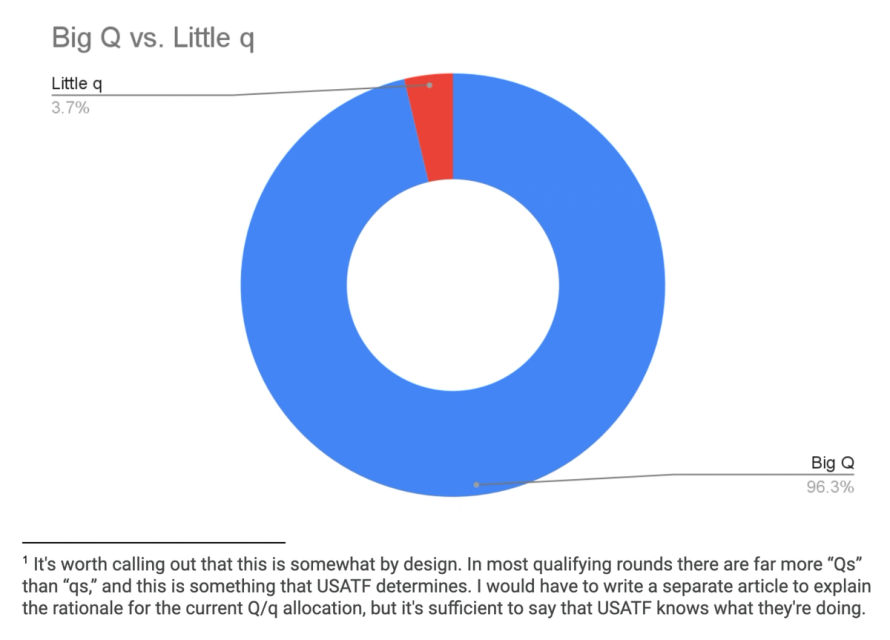

Another phrase you’ll often hear during trials coverage is “a Q is a Q.” An athlete can qualify to subsequent rounds in two ways. First, they can qualify based on their place (designated as a “Big Q” on the results). Alternatively, they can qualify on their time (designated by a “little q”). The common track adage that “all Qs are created equal” is accurate in that, regardless of qualifying type, the athletes end up competing in the next round. However, qualifying for the Olympics after making the final round in a little q is extremely rare. Only two athletes accomplished the feat this year: Juliette Whittaker in the women’s 800m and TeeTee Terry in the women’s 100m.

Even though the Olympic Trials aren’t as unpredictable as conventional wisdom purports, that doesn’t mean they’re not exciting. The US Olympic Trials are less about the potential for upsets and more about seeing the country’s best athletes compete. Because upsets are so rare, it makes them even more thrilling when they do happen. The consistent trend across events — where qualifiers are winning in early rounds — points to another saying, but this time it’s one that the data confirms: “winning is a habit.”

Rachel DaDamio

Rachel DaDamio ran at the University of Notre Dame and moved to Chicago after graduating to work as a data scientist, where she’s also training for a fall marathon.