By Kyle Merber

February 18, 2026

Kyle Merber dives into the stats behind elite marathoning.

It was a wild ending to the Seville Marathon with Shura Kitata Tola and Asrar Hiyrden Abderehman diving (re: falling) across the line a second under 2:04 in an almost collar bone shattering finish. Further down the results, it was a good day for the Americans, too: Daniel Mesfun (2:08:24), Andrew Colley (2:09:33), and Reed Fischer (2:09:47) all PB’d and dipped below 2:10, and Frank Lara wound up just on the other side. And Finland’s Alisa Vainio shaved nine seconds off her national record en route to victory, going 2:20:39.

But despite the excellent performances, my heart filled with shame as I digested the results—I had no idea Seville was this past weekend. But is that really my fault? To be a road racing fan in 2026 not only requires a good VPN and Internet sleuthing skills, but also a well organized and basically empty weekend calendar.

With the marathon enjoying an explosion of interest from lost millennial souls looking for a purpose, races are gaining larger fields and deeper pockets. It seems like every marathon has enough cash to draw in at least a few 2:05 guys and 2:20 gals now, which has seemingly made it more difficult to track when the next race worth following should be on our radar. Of course the World Marathon Majors remain appointment viewing, but how does the distribution of top performances compare to a generation ago? Are there actually more races producing world class times now than there used to be?

Now for a bit of inside baseball. The way I normally write an article for The Lap Count is that something happens over the weekend, which leads to a kneejerk hypothesis, followed by a deep dive into the data to see if my theory holds water. Well, this week I supposed that top marathon performances twenty years ago would have been more concentrated than the wide range of fast races we see today. Surely in 2005, everyone either ran Chicago or London, and it was not only easier to be a fan, but fields were deeper and the top athletes couldn’t avoid one another, right?

Right?!

Wrong.

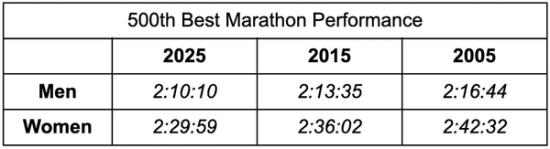

The numbers tell the opposite story. I took a look at the top 500 performances in 2025, 2015, and 2005, on both the men’s and women’s sides, for record-eligible courses. On prestige alone, a 2:42 in 2005 is worth a sub-2:30 today.

But what I was interested in is how many different races played host to each of these results. Last year, the men responsible for the top 500 marks ran them at 78 different events, and that figure was 96 for women.

In 2015 there was a distribution across 95 and 107 races, respectively, for the men and women. And in 2005 those performances were run across 96 races for the men, and 106 for the women.

Of last year’s 78 events, six races made up 36% of the top 500. If you are a dude looking to run under 2:10 in the marathon, then your best bet is to line up at Osaka, Valencia, Seville, Tokyo, Amsterdam, or Chicago. The women’s performances are not nearly as focused, perhaps because elite women are likely to have packs of men to run with if they venture outside the most conventionally fast courses.

Okay, enough numbers! What does this all mean?

Big picture, this is all net-positive—we want the top marathoners showing up to race each other as often as possible. That’s not their motivation though; time is. In 2024 the men’s Olympic standard was 2:08:10, and in the current 2028 cycle there’s speculation that the cutoff could be a minute faster. If the average elite marathoner’s schedule has room for two big efforts a year to hit that time, or chase absurdly fast shoe contract bonuses, then those swings can’t be wasted. An athlete needs to optimize to set themselves up for success, and a solo 2:09 on a hilly course doesn’t really do anything for anyone.

In the next few years, it’s reasonable to expect an even higher percentage of athletes will exclusively compete on those same few courses. This trend of flat, fast, bottle-heavy loops like the Marathon Project or the McKirdy Micro could become an increasingly popular destination for standard chasers if the economics make sense.

And that’s probably a good thing. We need consolidation. Times across the sport are broken, and comparing marathon results across time zones and topography is meaningless. Therefore head-to-head battles are the only barometer by which two athletes can fairly be compared. And when only three athletes per country, maximum, are selected for the Olympics, is the 20th place finisher really the 20th best marathoner in the world?

Of last year’s 500 fastest men and 500 fastest women, 676 hail from Kenya, Ethiopia, or Japan. We’ll never see all of them on the same starting line, but the fewer races they spread out across, the more we’ll understand about who’s actually the best over 26.2

Kyle Merber

After hanging up his spikes – but never his running shoes – Kyle pivoted to the media side of things, where he shares his enthusiasm, insights, and experiences with subscribers of The Lap Count newsletter, as well as viewers of CITIUS MAG live shows.