By Preet Majithia

February 10, 2026

World Athletics has amended the world rankings system, going into effect January 1st, 2026. This is important stuff for athletes, coaches, agents, and particularly nerdy fans to understand. However, to understand the changes, you need to understand how world rankings work.

Why should we care about world rankings?

You may be asking why you should even care about the world rankings. If you were to look at the top-ranked athletes in some events, they would not always be the person who won the last global championship, or who had the fastest, furthest, or highest performance in their event in the last year.

Although not perfect, world rankings are intended to be a representation of athlete consistency, placing particular emphasis on performance at big meets for their event.

However, there are a few key areas where the world rankings are important:

- They are often taken into consideration in whether athletes get invited to meets on the circuit. For those on the bubble, world ranking can determine whether they get into Diamond League races, and whether they may get an appearance fee or get travel and accommodation paid for.

- For qualification to World Championships and Olympics, World Athletics has stated that they would like to see only 50% of the athletes qualify by entry standard and 50% by world ranking. This is less relevant for 2026 with no full-scale global championship on the calendar

- They may factor into qualification for continental and other championships such as the European Championships and Commonwealth Games.

- Rankings will factor into fields for the World Ultimate Championships in September 2026.

- As a general metric for an athlete’s value relative to the rest of the market, brands may consider it when trying to decide whether to sponsor athletes. For World Indoors, the rankings are less relevant in most events, given the abbreviated indoor season.

World Athletics has adopted a slightly different qualifying system for World Indoors.

How do world rankings work?

To obtain a world ranking, an athlete has to compete in a certain number of competitions (for most events that’s five; it’s three for the 5000m and two for the 10,000m, marathon and multi-events).

For each competition, the time or mark is converted using the scoring tables. This provides a results score, which is intended to reflect the quality of the performance. The faster the time or the better the mark, the better the results score. In certain events (100m, 200m, 100mH, 110mH long jump and triple jump) there can also be a wind adjustment.

In addition, the athlete can be given a placing score for the position they achieve in the competition. A higher weighting is given to performances based on the significance of the competition. The most significant competitions are World Championships and Olympic Games, while the most important regular season meets are on the Diamond League circuit. The most significant marathons are the World Marathon Majors.

The performance score is the number that is then included in an athlete’s world ranking calculation.

Performance Score = Result Score + Placing Score

This means that, for example, a slower time to win a Diamond League meeting will give more points than a faster time run at a low-key meet. It is intended to reflect the (generally) higher quality of the competition that an athlete beats, and also to somewhat account for the conditions on a given day at any higher category meets.

Each athlete is then given a Ranking Score which is calculated as the average of the five, three, or two performance scores, depending on the event.

Performances from ‘similar events’ can be included, but at least three of the five performances (or two out of three in the 5000m) need to be from the athlete’s main event. For example, an athlete’s 100m ranking needs to have at least three 100m performances, but then can also include two 60m performances.

The ranking period for the world rankings found here on the World Athletics website is the last twelve months. However, the world rankings that are relevant for a different competition may be over a different period. For example, for the European Championships, the ranking period is from July 27th, 2026, to July 26th, 2027, and you would need to access the relevant ‘Road To’ online tool to see the correct world ranking information.

Placing Scores and the 2026 changes

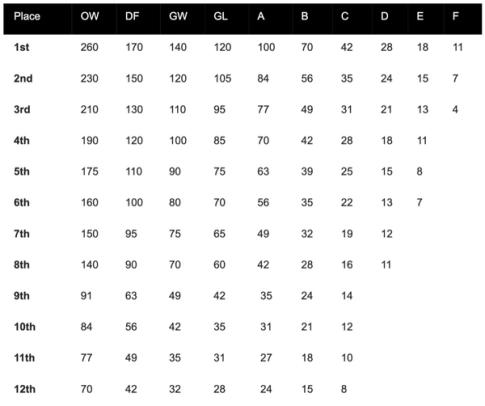

The key change to the ranking system for 2026 is that World Athletics has implemented a reduction in the placing scores for each category of event.

As an example: The new placing points tables reduce a win at a meet like the Diamond League (GW category) from 200 placing points to 140 placing points.

Another change is that placing points go deeper in racers for the higher category meets, so coming in 10th place in a Diamond League 1500 gives you the same points as winning a 1500m at a Category C meet (such as a Continental Tour Bronze meet).

An example of the impact of these changes is that at the end of 2025, the No. 1-ranked 1500m runner in the world was Nelly Chepchirchir, who had three Diamond League wins, including the Diamond League Final. No. 2 was Jess Hull, who had on average run faster times.

Nelly’s average result score was 1,229.6, which equates to a 1500m time of 3:57ish on the scoring tables. Under the old scoring system, she had 1,060 placing points and a combined average performance score of 1,431 points. Under the new scoring system, she had 710 placing points, and her blended performance score is therefore 1,372 points.

Jess’s average results score was 1,239.8, which equates to a 1500m time of 3:55.9ish on the scoring tables. She had a total of 950 placing points across her five performances, resulting in a combined average performance score of 1,429, just below Nelly’s score of 1,431. Under the new system, she gets 674 placing points, so her average performance score increases to 1,374 points overall and she overtakes Nelly. It is also worth noting that she did not win any of the five races from which these performances were taken to give her the world ranking. However, she becomes the No. 1-ranked 1500m runner by virtue of running fast at big meets and coming second or third each time.

Winners and Losers

Although it remains to be seen what the exact impact of these changes will be, it’s likely to incentivize athletes to focus on posting fast times or stronger marks in conducive conditions, rather than focusing on the biggest meets with tougher competition.

Big Winners:

- The Boston University indoor track, as well as “Throw Town,” a.k.a. Ramona, Oklahoma will likely be more popular than ever!

- Americans—The U.S. has only one Diamond League and only a couple of gold-level (Category A) meets, which means many U.S.-based athletes typically head to Europe in the summer for higher-ranking meets. So this could reduce the incentive for Americans to go race their best competition on the European circuit.

- Pace lights—these guys are here to stay!

Big Losers:

- Head-to-head competition—there’s less incentive for top athletes to make the trek to the Diamond League and race their biggest competition. The circuit may see a reduction in depth if the travel isn’t worth it for everyone.

- The early season Diamond Leagues—historically, there were many athletes who would travel out to China, Doha, and Rabat to participate in these early season Diamond Leagues where weaker fields meant more points were up for grabs. Could these changes reduce the incentives for both European and U.S. athletes to deal with the long travel to compete at these meets?

- Let’s wait and see what these changes bring to the big European meets. Will fewer U.S. and international athletes choose to hit the European circuit? The likelihood is it will still be the place to chase fast times in the summer. In sprints, the fastest times tend to come with better competition. In the distance races, they need to be well set up with good pacing and a strong enough field to hang with the pace once the rabbits drop out. Not to mention that in the summer, conditions become mighty unfavorable for fast distance running across the majority of the U.S.

Quick Takes On The Changes

Kyle Merber: To sparknotes the change: World Athletics has decided that how fast you run should be weighted more heavily than how competitive the field you beat was—compared to how it used to be. In my opinion, that’s the opposite of what we should be trying to do. Now it’s basically saying, “Why would you even bother going to a Diamond League and racing the best athletes in the world, when you could just run as fast as possible in a time trial at BU?”

Historically, rankings rewarded athletes for going to the biggest meets with the toughest competition to earn that place score. Now that factor isn’t valued as much. We’re essentially saying, “Just go run fast. It doesn’t matter where.” And I don’t love that.

Even though this helps Team USA, I don’t love the system. Just because we’re from America doesn’t mean we don’t want to see American athletes go overseas and compete against the best. I’d actually argue the opposite. As noted in the USATF article, like, the U.S. saw improvements in 80% of events (meaning in all by 8 events) because of this change. But what we really want is to force U.S. athletes to go wherever the best competition is and race them. Now it’s flipped.

(Update: Lia Skoufos, the author of the USATF article, later shared with us that 62.9% of US athletes in the top 100 improved (415), 18.9% stayed the same (125), and 18.2% decreased (120))

There’s no perfect way to do it, but ideally, you’d factor in the rankings of everyone an athlete beats and let that influence the place score. So even if it’s at BU, if you beat ten guys who are ranked in the top 20, that should matter in how much you’re rewarded. But there’s no clean way to do that. So instead, it becomes, “Which meets offer the biggest prize money?” and we just assume those are the most competitive.

Preet Majithia: I think the reason World Athletics made this change is that the old system was skewing the results too much. You ended up with some slightly strange outcomes in the rankings. For example, last year Melissa Jefferson-Wooden was not ranked as the world’s top 200-meter runner… Brittany Brown was, largely because she had won a few Diamond League races.

That illustrates the core issue. Ultimately, when you look at the top of the rankings, you expect the athletes who have run the fastest times to be the best athletes. Most of the time, that’s true. There are exceptions (last year with Azeddine Habz, for instance) but in the vast majority of events, the athletes who run the quickest, throw the farthest, or jump the highest are generally the ones who should be ranked highest.

If an athlete has done that consistently across five meets, that’s arguably more representative than someone who cleans up ranking points at a handful of Diamond League meets, particularly when those meets are in regions where many of the top athletes in that event haven’t shown up. At that point, it becomes a bit of “playing the game,” and I think this change is an attempt to reduce that.

I can understand the rationale, and in some ways it does make sense. For example, if you’re a local athlete who gets a host-nation entry into a Diamond League, you can pick up significant ranking points simply by being there. That can boost your chances of qualifying for major championships over another athlete who may be equally (or even more) talented, but hasn’t had access to those same high-level meets.

So there is logic behind the adjustment. The weighting may simply have been too skewed before. That said, it’s hard to know whether the recalibration has landed in the right place, because there’s still a real risk that fast times get incentivized too heavily. BU being the obvious example.

Keep up with all things track and field by following us across Instagram, X, Threads, and YouTube. Catch the latest episodes of the CITIUS MAG Podcast on Spotify and Apple Podcasts. For more, subscribe to The Lap Count and CITIUS MAG Newsletter for the top running news delivered straight to your inbox.

Preet Majithia

Preet is a London based accountant by day and now a track fan the rest of the time. Having never run a step in his life he’s in awe of all these amazing athletes and excited to help bring some attention to the sport.